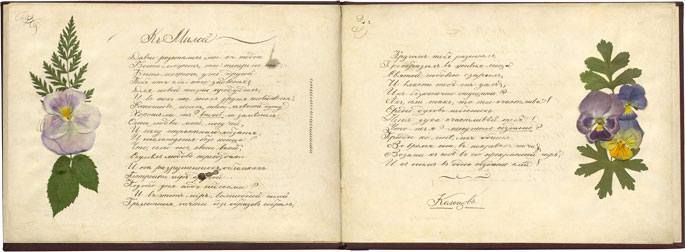

Amdist the blue mist of the sea...

What does it seek in foreign lands?

What did it leave behind at home?

Waves heave, wind whistles,

The mast, it bends and creaks...

Alas, it seeks not happiness

Nor happiness does it escape.

Below, a current azure bright,

Above, a golden ray of sun...

Rebellious, it seeks out a storm

As if in storms it could find peace!

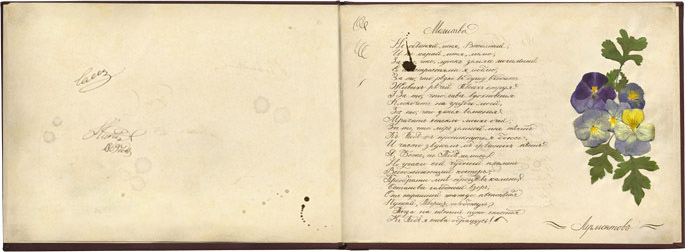

| Lermontov |

|

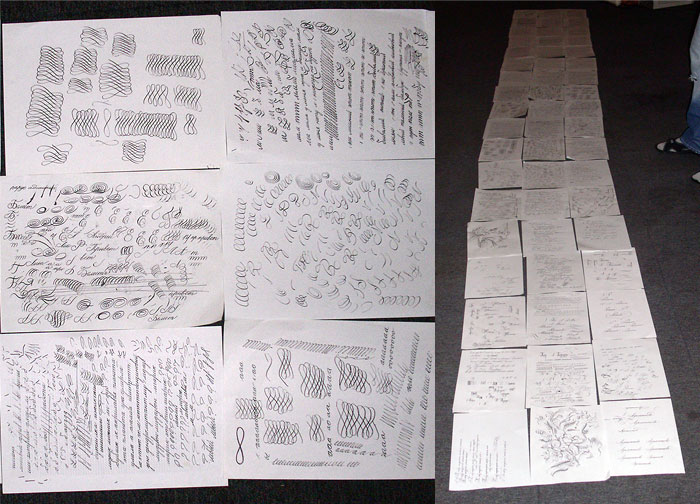

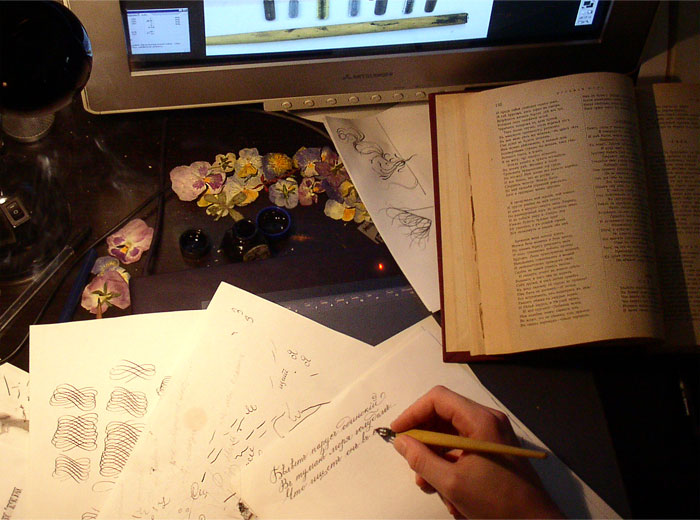

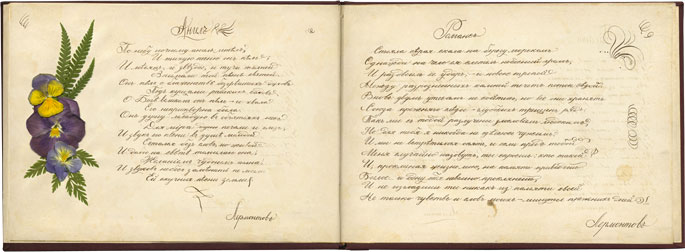

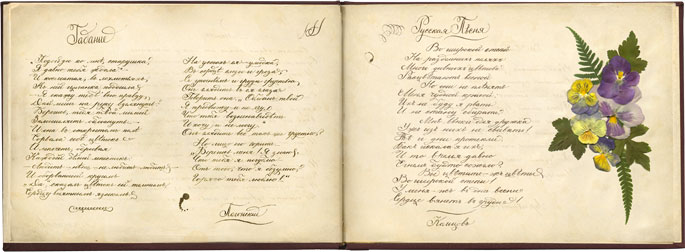

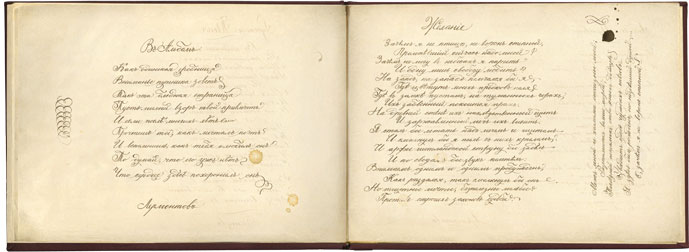

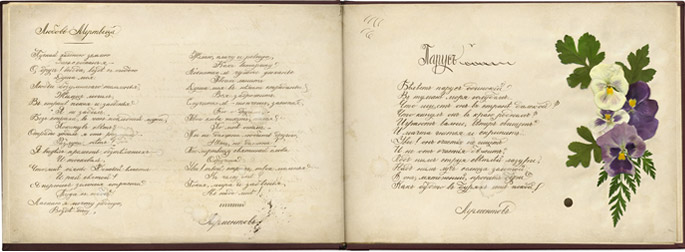

Iron gall ink. In Russia, as well as in Europe, iron gall ink was standard drawing and writing ink till the 20 century. But the problem was that such writings faded to brown. That’s why old manuscripts appear so quaint.

In other words, the writing did not only fade but it showed through on the other side of the page even on thick paper. This flaw doesn’t visually spoil old letters and documents. Quite the contrary—it makes them fascinating. The mirrored text seen through the paper makes it more amusing to read. |

|

|

Application. We turn our herbarium into small bouquets. |

|

|

And let the glue dry. Spots right there. The pages aren’t supposed to look too tidy, so we dilute the text with tears, blots, some stains of other kinds, corrections, underlines and flourishes. |

|

|

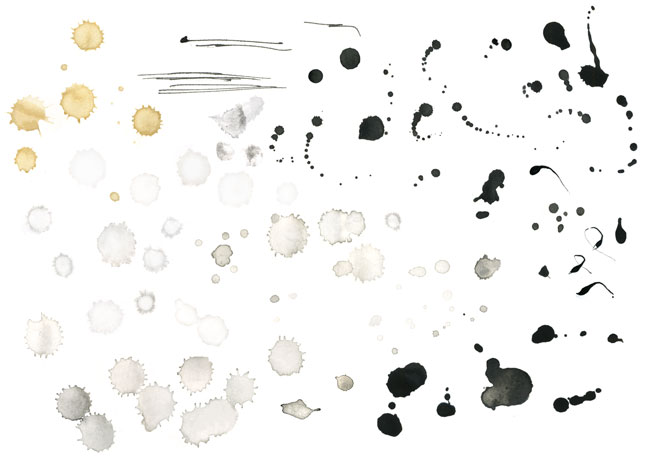

It turned out that the right blot is hard to make. Here are three most frequent blots: |

|

|

|

Nostalgia. It is likely that Molly had the poems written down in her album in her gymnasium years. And now the album is nothing more than a token of childhood. We assume that this album dates back at least 10 years and the paper should already be yellowish. In the bedroom the album is in the shade, so its pages lose some contrast. We intentionally overintensify the paper texture because we do not want the pages to look too pale. |

|

|

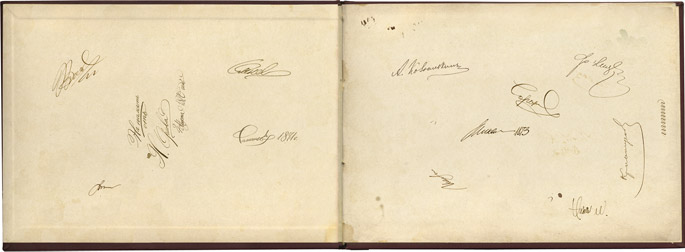

On the first pages we put the autographs that authenticate this album. We bring together the rest of the pages and here it is—a common late 19th century girl’s album. |

|

|

A keepsake. We’d better fold this intriguing note that got lost somewhere between the pages. This is a purely sincere love letter addressed to Molly, but the reader shall never know what it said.

Love Faithfully yours M. (To be continued.) |

|