Brought to your gracious attention

illustrations for Table Talk 1882 project

(Based on B. Akunin’s book of the same name)

|

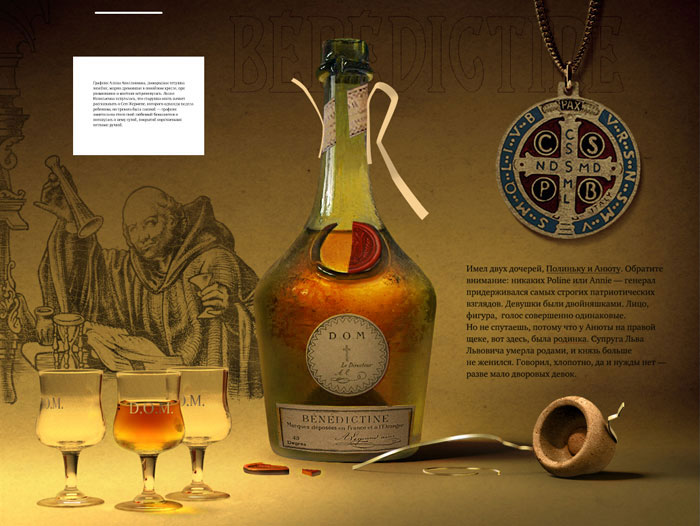

Issued regularly 18 December, 2005 Chapter SixContents: Sticking a bottleneck out. — Drinking brotherhood. — Bottoms up! — W.T.F. — One for the road. In this chapter the reader learns about a strong flavoured liqueur (43% vol.), an amber yellow drink with sweet (320 g/l sugar) bitterish taste that was first made by Dom Bernardo Vincelli in 1510, at the Benedictine Abbey of Fécamp in Normandy (France). And today it continues to be produced on the shore of La Manche Bay. We shall start.

Sticking a bottleneck out.

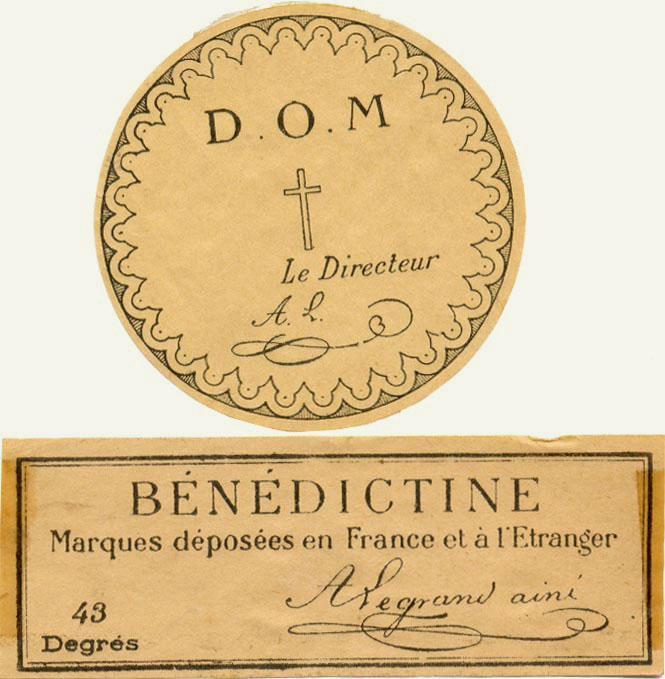

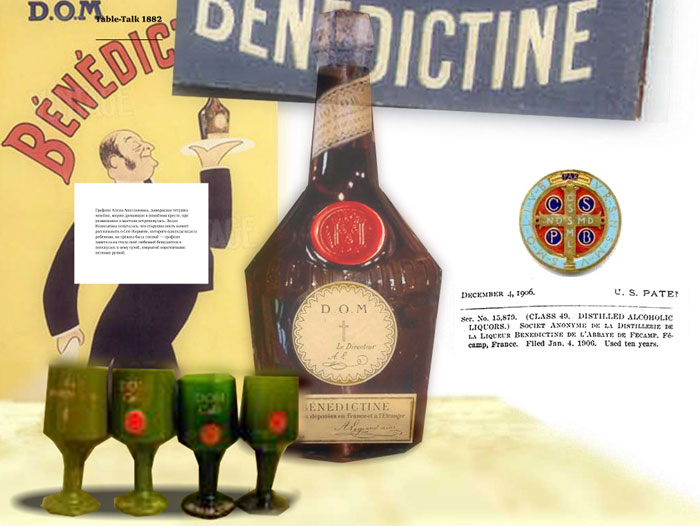

What could we possibly use to illustrate the scene? Apparently, we’ll have a bottle of Bénédictine, wine glasses, maybe the St. Benedict cross and a couple of posters of the time. As usual, we make a draft first to see general composition.  Lets draw the elements.

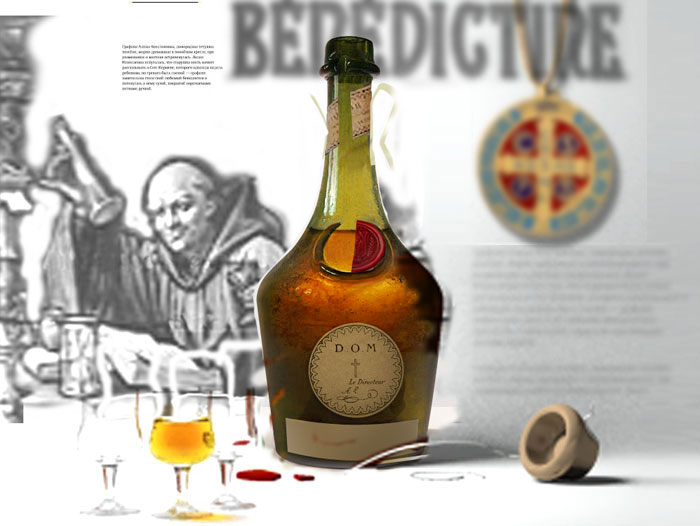

Corks back then were a little different from those today. What’s the deal—we find one to paste it into the scene.  Such a bottle sure asks for a different background. What can we put up instead of the posters? Lets reread the history.

Drinking brotherhood.

The history of Bénédictine goes back to Renaissance. Dom Bernardo Vincelli, a stranger pharmacist, developed an elixir (a liqueur in essence) that is believed to help to preserve health and live longer. It comprises a suite of 27 herbs and spices from all over the world.

This liqueur was especially loved by King Francisc I to whom Bénédictine owes its popularity. The recipe was lost during the French Revolution and gained back only in 1863. Allegedly, Alexander Le Grand, a local wine merchant, found an old manuscript from the ravaged abbey library with a ciphered recipe in it. He managed to decipher it. He modernized the recipe (it is said that now Bénédictine uses 75 medical and aromatic herbs), recreated the liqueur and marketed it under trade name Bénédictine. He became rich and build a Bénédictine castle museum in Fécamp. One of the panels there depicts the monks making the liqueur.  That would make an excellent background!

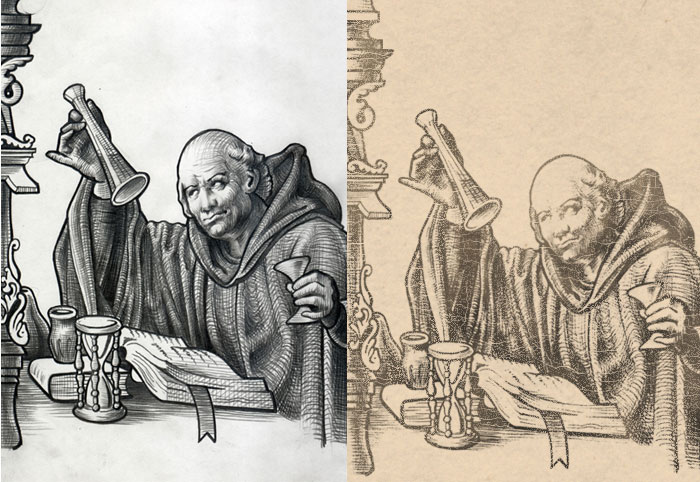

Lets try to make an imitation of engraving.

Now, we dim the background and pass on to the wine glasses.

Bottoms up!

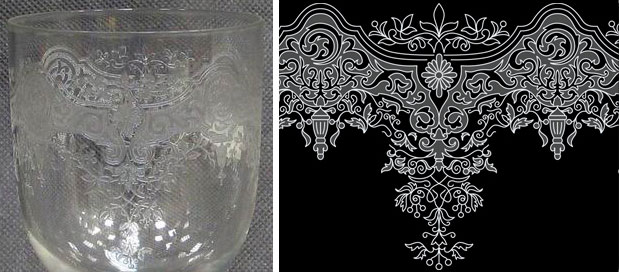

We need the end of the 18th century wine glasses. Lets get hold of some drinkware of the time.  Most of the glasses had simple or pantograph engravings. We’ll take the more complicated pantography. What we have here is an incised vegetative ornament, we copy it…  …and put in on the glasses.

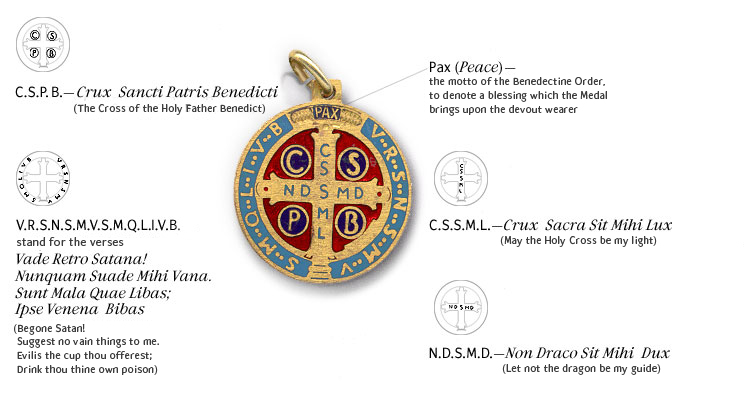

W.T.F.

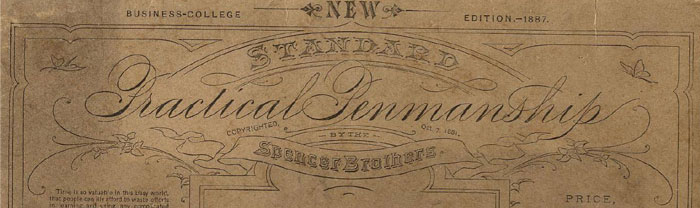

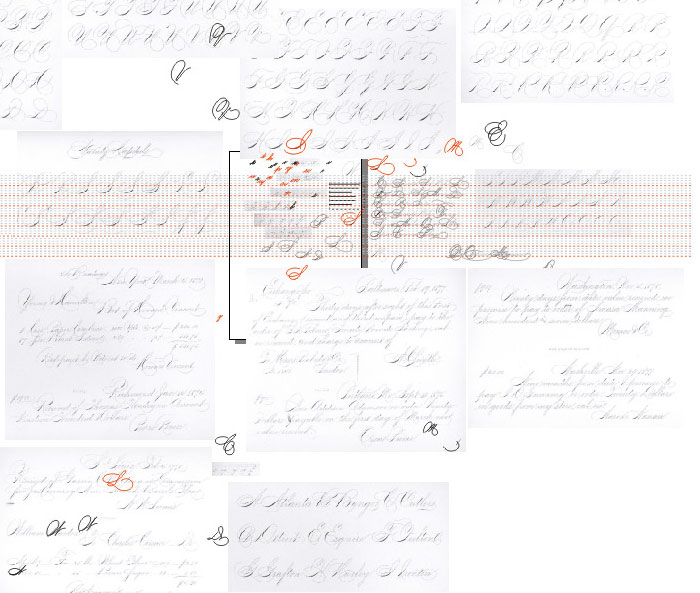

It is time to introduce some text elements. Besides the label, we have the St. Benedict Cross. What are these letters? Lets see—we grab a looking glass.  It may well be that the Benedictines were muttering this Latin pray while making the liqueur. We are going to have it near the cross. We find the late 19th century samples of writing.  Study it:  And write down the pray:  Doesn’t it look wonderful?

One for the road.

In the end we should make the whole thing somehow special. Well, alcohol is the keyword so we are going to “buzz it up.” We take a trip to Yura Mikhailov’s country house to make a scientific research on the defocusing as a function of the variable drunkenness.

Move the cursor around.  An-n-no-ther-r shh-ot, pleez!  (To be continued.) |

Narrated by Vasya Dubovoy |